Are domesticated dingoes affectionate? They can be — if they exist.

What does it mean to be a “domesticated dingo”? I’ll share a brief overview as well as our experience with our rescue dingoes, Rusty and Jalba. This might be an interesting read if you’re thinking of adopting a dingo in Australia. Keep in mind that this is our personal experience — all rescue dingoes are different.

Key notes

- Australian dingoes are not a domesticated species, however archeological research suggests some dingoes were domesticated, in specific settings.

- Never approach a wild dingo. If you see a dingo in distress, call your local wildlife service.

- Some rescue dingoes enjoy pats whilst others prefer not to be touched.

- They may show affection through enthusiastic greetings, licking, booping and more.

Short on time? Jump to:

- What does it mean to be a domesticated animal?

- Domesticated vs tamed animals

- Can a wild dingo be tamed?

- Are our rescue dingoes tame?

- Are dingoes affectionate?

- How our dingoes show affection

- Frequently asked questions about our rescue dingoes and affection

What is a “domesticated dingo”? Do they exist?

In a colloquial sense, most of us probably consider a domesticated dingo as a dingo who lives in a home environment with humans. This definition, however, isn’t accurate, and when it comes to dingoes, definitions matter.

What does it mean to be a domesticated animal?

Well, that depends on who you ask.

The definition of what it means to be a domestic animal differs: In The Conversation, Dr Loukas Koungoulos, Professor Jane Balme, Dr Shane Ingrey and Distinguished Professor Sue O’Connor differentiate between the traditional view and newer perspectives, stating that “newer perspectives focus on long-lasting relationships between people and animals.”

In The Conversation, they discuss dingo burials excavated from the Curracurrang archeological site in NSW’s Royal National Park and what they reveal about Australia’s First Nations people and their relationships with dingoes.

“The act of burial implies a degree of care and belonging in a community. Some archaeologists argue animal burial is a fundamental sign of domestication”.

Koungoulos, Balme, Ingrey and O’Connor analysed the dingo skeletons from the site which had not previously been studied. They found that the earliest these bones were buried was around 2300-2000 years ago and that the burials at this site continued until the colonial era. Some of the dingoes were pups, whilst others were adults, 6-8 years old.

They found that whilst not all dingoes were domesticated in ancient times, “some dingoes, at least in certain settings, were domesticated. This doesn’t mean all dingoes were domesticated, nor does it conclusively indicate they originate from domestic dogs. Most dingoes were, and still are, wild animals…”

If we look at genetics, the definition of what it means to be a domestic animal differs.

National Geographic journalist Natasha Daly defines domesticated animals as those which have been “selectively bred and genetically adapted over generations to live alongside humans”. Further, domesticated animals are bred and adapted for specific purposes, such as companionship, food and work.

Dr Michael Purugganan, a Professor of Biology at New York University (NYU) states that domestication “is a coevolutionary process that arises from a mutualism, in which one species (the domesticator) constructs an environment where it actively manages both the survival and reproduction of another species (the domesticate) in order to provide the former with resources and/or services”.

Are dingoes selectively bred and genetically adapted over generations to live alongside humans? No. In Australia, dingoes are wild canines, who live and breed in the wild. In Australia, we don’t breed dingoes for companionship, food or work — they don’t plough the fields, round up sheep or carry Aussies across the Nullarbor… however if we consider the long relationship between First Nations people and dingoes, it might be fair to say that whilst dingoes, as a species, have not been domesticated, some dingoes, in some settings are…..

Domesticated animals vs tamed animals

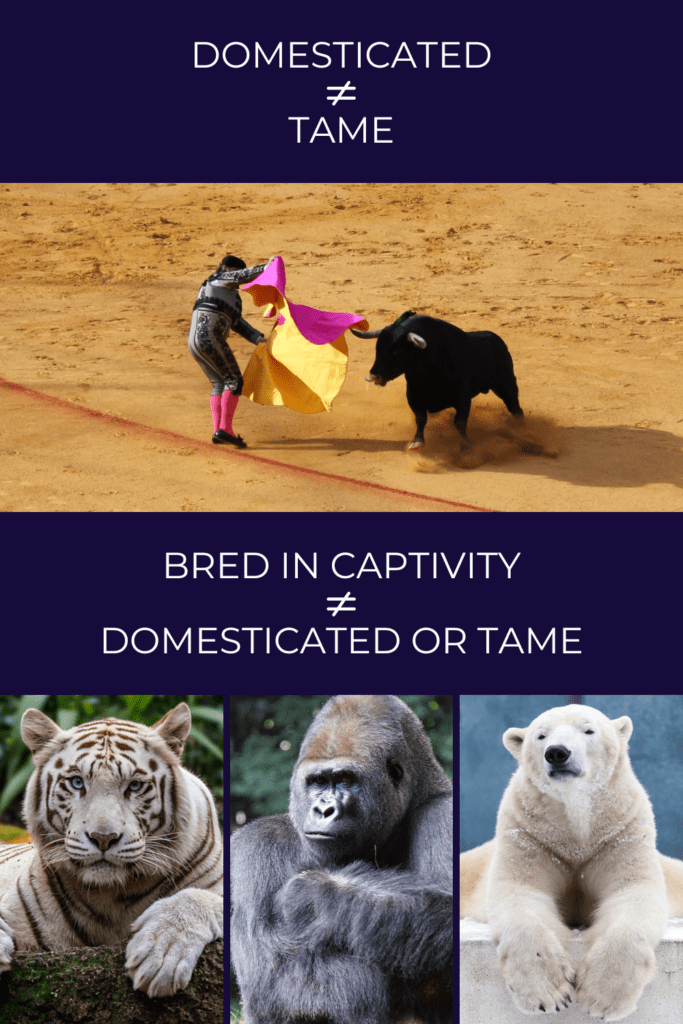

In National Geographic, Daly points out that there is a difference between domesticated animals and tamed animals (not that a dingo is tame).

“Domestication is not the same as taming. A domestic animal is genetically determined to be tolerant of humans. An individual wild animal, or wild animal born in captivity, may be tamed—their behavior can be conditioned so they grow accustomed to living alongside humans—but they are not truly domesticated and remain genetically wild.”

Dr Carlos A Driscoll, Dr David Macdonald and Dr Stephen J O’Brien state that “taming is the conditioned behavioral modification of an individual; domestication is permanent genetic modification of a bred lineage that leads to, among other things, a heritable predisposition towards human association.”

Australian dingoes which live in home environments are conditioned to live with humans, they are not permanently genetically modified.

Driscoll, Macdonald and O’Brien point out that domesticated animals might not be tame, and tamed animals might not be domesticated. Consider a Spanish fighting bull, which is domesticated, but certainly not tame, or a dingo adopted as a pup, which is possibly quite tame but not domesticated. Further, Driscoll, Macdonald and O’Brien note that not all animals which are bred in captivity are domesticated: consider tigers, gorillas and polar bears.

Rusty and Jalba were rescued from the wild and tamed (to a point!), but they are not considered “domesticated”.

While some approaches differ in their definition of what it means to be a domesticated animal, the role of dingoes in First Nations’ culture is clear: “The Dingo is deeply sacred to Australia’s First Nations peoples. They are family.” Click here to read more about the National First Nations’ Dingo Declaration.

NEVER TAKE A DINGO FROM THE WILD.

IF YOU SEE A DINGO IN DISTRESS,

CONTACT YOUR LOCAL WILDLIFE SERVICE.

Can a wild dingo be tamed?

Most would argue that a wild dingo can never truly be tamed, but they can be taught to live in a home environment — not that you should ever take a dingo from the wild.

Dingo and wildlife rescues often care for dingoes who have been orphaned in the wild or displaced from their habitat. Once rehabilitated, these wild-born dingoes often end up living in domestic environments with humans (but this is not the same as being “domesticated”).

Rescue dingoes who live in a residential environment will always retain wild characteristics, for example:

- Australian dingoes are apex predators — they possess a high prey drive, which means their ability to detect prey is exceptional. For this reason, adopting a dingo when you have pocket pets is not recommended.

- Dingoes are pack animals but they are also very independent creatures: reliable recall is not likely and if you expect them to “sit”, “middle” or go to “place” for no reason, you’re likely to be disappointed.

- Dingoes are escape artists — they can learn to stay within safe boundaries (but it doesn’t mean they will!). Your property must be secure, otherwise you’ll discover dingoes are proficient diggers and smart problem solvers who aren’t deterred by fences, gates or latches.

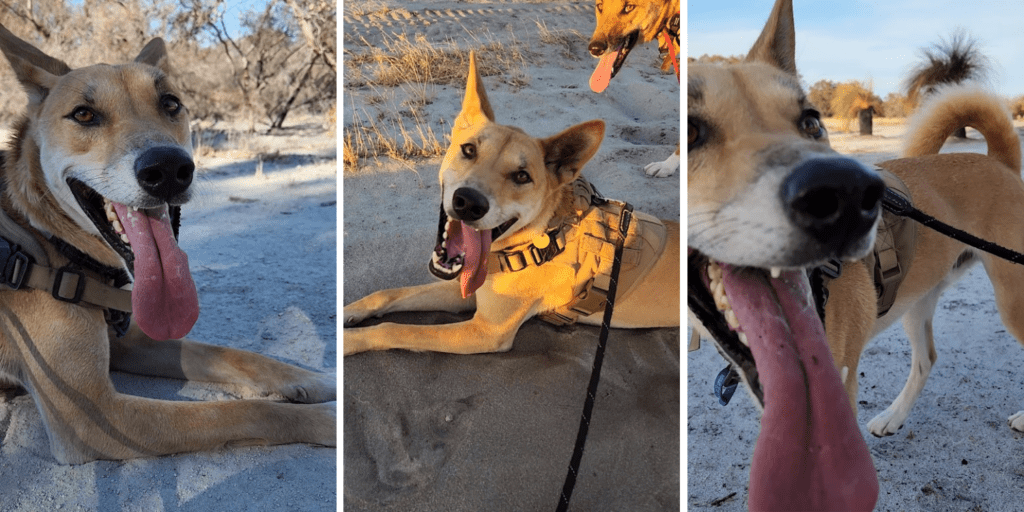

Are our rescue dingoes tame?

Yes, to a point. They certainly live with us harmoniously and even seem to like us — we could go as far as saying they love us and they feel we are in the same pack. We obviously don’t know that for sure, but their behaviour suggests something along those lines.

If we consider that tame animals are comfortable in or tolerate the presence of humans, then we could say that our rescue dingoes are relatively tame. Rusty and Jalba relax when they’re at home with us, peacefully wandering around the house and falling asleep in various corners of the house and yard.

Australian dingoes have a strong fight or flight response and usually shy away from humans and anything that could be dangerous. Although they’re very comfortable with us, they’re still wary of anything unusual, such as new, large boxes, new people, strange scents on our clothes and even if we’re holding something like a tissue.

Our dingoes:

- are toilet trained (thanks to SAFE Carnarvon)

- don’t jump on the dining table or kitchen bench (anymore!)

- sit and wait before eating

- wait before exiting a car

- know which rooms are out of bounds

- don’t chew on furniture (anymore).

Although they are tame enough to live in our home, they display typical wild dingo characteristics. Rusty’s prey drive is very evident, he displays incredible instincts and hearing, whilst Jalba is less likely to detect small animals such as lizards. Both have unreliable recall but do respond to their name and come when called in a home environment where there are less distractions.

Rusty also has a tendency to hide extra food and soft toys: he digs a shallow hole, drops his treasure and buries it with his nose. Jalba, on the other hand, likes to stand beside me in the kitchen and woo me with his beautiful brown eyes until I give him treats — I don’t think I’ve ever seen him bury food or toys.

An important note: Rusty and Jalba have lived with us for over three years, after being orphaned as pups. They are somewhat tame but never expect a wild dingo to be tame. Never approach a wild dingo.

Australia has had a few challenges when it comes to dingoes and humans, so before you walk around K’gari patting wild dingoes and taking selfies: never, ever approach, feed or capture a wild dingo, no matter how tame you think they are. Wild dingoes have a strong fight or flight response: if they can’t flee, you may find yourself getting nipped. This results not only in injury but the dingo may be euthanised for an action that wouldn’t have occurred if they had been left alone.

Are dingoes affectionate?

First, let’s recap: never approach a wild dingo. Below, I’ll describe what it’s like living with wild-born rescue dingoes and how they show their affection.

Australian dingoes are naturally aloof — but, like any animal, they each have their own personalities.

Rusty was adopted as a pup but didn’t come to our home until he was two. He lived in a few homes, including one where he could run free and return home each night, which is probably why he displays more typical dingo characteristics than Jalba.

Jalba was rescued at about four weeks old, so he has lived in home environments for most of his life. He’s more gentle, less interested in prey and less likely to escape.

Despite living in homes for most of his life, Jalba is just as aloof as Rusty. Most dingoes are not lapdogs, but many will gladly share the couch or your bed, or lean on family members for a pat. In our home, beds are off limits, but they love to be in the same room as us.

How our dingoes show affection

We get the impression that Rusty and Jalba feel happy and content in our home, that they love us (or at least like us a lot!) and are happier when we’re all together.

This is how our dingoes show their affection:

Calmness: If you come into our home and our dingoes are comfortable enough to be calm, or go to sleep, it’s the ultimate compliment. It means they feel comfortable with your presence and they might even like you. If they’re not calm, it could be for any reason, such as feeling overwhelmed by new scents, sounds and people.

Morning greetings: Nearly every morning, Rusty is waiting for me at the end of the hallway, tail wagging and eyes full of expectation. If he’s not there, as I exit my room I hear him leap from their bunk bed and Jalba slowly rise and stretch. They like to shepherd me out of the hallway and into the next room, tails wagging, noses booping my legs and bodies pushing me in the right direction. We sit outside together while they relish their morning pats, standing or sitting beside me, leaning on me and booping me. Unless they’re in a deep sleep (common in winter!), they greet each of us when we wake in the morning.

Greetings when we arrive home: They absolutely love when we return home. When a family member arrives home, I’m in awe of Rusty’s ability to detect their cars — the way he wakes up, tilts his head and strains to look towards the front of the house. They anticipate with excitement, running back and forth, in and out of the house, trying to look to get a glimpse of who has arrived and checking if they’ve come in the front door. Back and forth, back and forth, talking with each other about how darn excited they are and “did you hear that, did you hear that — s/he’s back!!!”.

When we open the front door, we’re greeted with the sweetest, deepest “arrrrroooo” from Rusty, sometimes more than once. Jalba only “aroooo’s” on the odd occasion. Sometimes Rusty will look at us, run away and come back, and sometimes stand on his back paws to greet us. Jalba comes in for a rub, leaning on us. They also love to sniff us, especially after going to new places or after we’ve eaten. In Dingo, Brad Purcell states that:

Dingoes and other canids use their nose to identify individuals that they know and to identify other information such as where pack members have been and maybe even what they’ve eaten… The scents on the breath of fellow pack members may indicate if that animal has food for the rest of the pack or if it found an interesting scent that the other pack members need to familiarise themselves with.

So perhaps they sniff our breath to find out where we’ve been and what we’ve eaten — seems likely? When we arrive home Rusty likes to lick us, but Jalba is not as keen. Home greetings usually take 5-15 minutes.

Rusty doesn’t quite say hello — he says “arrrroooo”, but here’s a great video of Dundee saying hello (thanks Wildlife Twins!):

Leaning: Sometimes they lean on us, asking for a pat. Leaning away also communicates that they’ve had enough of an interaction or are uncomfortable.

Approaching: Sometimes Jalba seeks affection by walking up to me and just standing there until I give him attention: pats, compliments, a head rub — he’ll take it all, just don’t bring a brush near him.

Booping: They often boop us with their noses, especially when they’re greeting us, want attention or to be fed! When I’m standing, I’ll often feel a little boop on my leg and I look down to find Jalba looking up at me, waiting for pats and kisses.

Licking: Jalba doesn’t usually lick us but Rusty does if he’s extra happy or if we have an interesting scent.

Proximity: They love being in the same room as us — I’ve been told this is because they are pack animals, and we are part of their pack. They love company and are very spoiled, I’m only metres from them for most of the day. If we allow them into our room, they love to curl into the corner and sleep — they love our company.

Following: When they’re not sleeping, it’s not uncommon for our dingoes to follow us around, especially if we’re preparing food. They don’t follow us for very long and will either return to their bed or sit or lie down in our sight, showing they’re being good and deserve a piece of chicken or cheese.

Cobbing: This one is not about us, it’s about Rusty and Jalba. Cobbing is when a dog or dingo nibbles on another dog or dingo, similar to when humans eat corn on a cob. Jalba loves to cob Rusty, which I’ve heard is a sign of affection.

Playing: Our dingoes have very little interest in typical dog toys such as balls and ropes, but they love running around and playing with each other and with us. They like chasing, being chased, wrestling and any game that involves food.

Jumping: I don’t remember Jalba ever jumping on us, but Rusty likes to do it when it’s playtime. He either jumps straight at us or stands on his back paws and lands with his front two paws on our arms or bodies. He is the crazy one.

Gazing: Rusty will make brief eye contact when he wants something, and when he really wants something such as food outside of his normal meal time, he’ll maintain very steady, sustained eye contact. He combines this with very loud, very clear talking. I don’t know if he “says” the same thing each time, but he’s definitely saying something. Super super cute. Jalba is more of a romantic with the sweetest little puppy eyes — he looks into our eyes and we usually can’t help but say “awwwwwww”. Jalba enjoys eye contact for longer periods, particularly while we’re fussing over him and giving him a rub. He does, however, give us the side eye if he doesn’t want to be disturbed, or he’ll open his eyes quite wide, rather than displaying a soft gaze. For newbies, I highly recommend NOT making eye contact with a dingo, especially one who doesn’t know you. Avoid staring at a dingo as this can be perceived as a threat (although I have heard one view that states the opposite).

Not stealing: They’re very strategic when it comes to stealing our belongings, especially Rusty. It’s as if they know we’ll get upset if they take our belongings. They rarely take anything of importance (except one limited edition sock), instead, taking items such as tissue boxes, the odd tea towel and cardboard materials we keep for their enrichment. Stealing food is a little different… Rusty can be opportunistic when it comes to food. On rare occasions, Rusty has quickly taken food from the bench, our plates and even our hands. I don’t think we’ve ever seen Jalba steal anything, other than clothes pegs.

Frequently asked questions about our rescue dingoes and affection

Do your dingoes sleep in your bed? No, but that’s our choice, we don’t normally let them in our bedrooms. There are other dingo guardians who allow their rescue dingoes to sleep in their bed but we don’t, simply to make cleaning a bit easier, and, TBH, Rusty likes to let one rip every now and then, so…

Do you hug your dingoes? Yes, but on their terms. They tolerate a gentle hug when the time is right. We never hug them tight and we always pay attention to signs that they’ve had enough, for example, if they lean or step away.

Do you kiss your dingoes? Yes, but we only started doing this recently. Our kisses are cheek-to-cheek or on top of their head or nose.

Do your dingoes like being patted or stroked? They love when we pat them, unless they’re trying to sleep and don’t want to be disturbed. Sometimes as they fall asleep, they seem to like being stroked, especially on their head, but it depends on if they feel relaxed or not. In most cases, they don’t like being patted or stroked by people outside of our immediate family. Some rescue dingoes don’t like being patted by humans — it’s important to remember that every rescue dingo (or dog) has its own experiences and preferences that shape their behaviour.

I don’t have a recent video of our dingoes to share but here’s a video of Fred, Adina and Simba enjoying dingo cuddles at The Australian Reptile Park:

How often do your dingoes sit on your lap? Never. They have no interest in sitting in our laps but do enjoy sleeping in rooms that we’re in and occasionally on the couch, if we let them.

Do your dingoes like being picked up? They don’t seek to be picked up but it’s important they are comfortable with being picked up in case of emergency or for medical reasons. For this reason, we pick them up once in a while to help them stay familiar with it, but only briefly.

Do your dingoes roll onto their back for a belly rub? Rusty very rarely rolls onto his back, but he’ll roll onto his side for a good rub and lift his paw. Jalba often rolls onto his back while he sleeps, paws in the air, but he doesn’t stay in that position if anyone approaches.

Do dingoes wag their tails if they’re happy? They do! Jalba is missing most of his tail due to an injury when he was found, but they both wag their tails when they see us. They wag their tails from excitement and happiness but they also wag their tails slowly from side to side if they’re up to mischief or ready to play.

Rusty looks like he’s smiling in some photos — do dingoes smile? I’m not a dingo expert, so I’m not sure if dingoes smile, but it would be accurate to say that ours don’t. Sometimes they look like they are but it’s probably just a coincidence and it’s hard to catch them “smiling”. The photos we have of Rusty “smiling” were taken while he was resting during a walk, their “smiles” never seem to be in response to something that makes them happy. In Brad Purcell’s book, Dingo, he mentions a few dingo facial expressions and smiling is not one of them, instead there are four: normal and calm, anxiety, threat and suspicion.

How does your dingoes’ fight or flight response affect their affection and how cuddly they are? We always ensure our dingoes have an “out” — we never block them into a corner or hallway. They need to have the option of moving away, which means not holding them firmly or tightly unless absolutely necessary. We never force them to engage in an interaction and we always advise our guests not to pat or attempt to pat our dingoes. We know some other rescue dingoes are a little less “flighty” whilst some rescue dingoes do not like to be touched, even after living with a family for a few years — each dingo has its own personality and its own experiences which shape their behaviour.

Does this mean you visitors never pat your dingoes? No. Our dingoes become comfortable with some “new” people very fast and will even sleep in their presence. For most people, however, it can take a few visits to build up trust and it’s important not to pat them until we suggest it is okay. When first meeting our dingoes, we ask our guests to ignore Rusty and Jalba and to allow Rusty and Jalba to approach when they feel ready, rather than guests approaching our dingoes.

What are your dingoes like with children? Our youngest child was ten when we adopted our dingoes. Young children tend to be quite affectionate with their pets, so it’s not necessarily a good idea to adopt a dingo if you have young children. Click here to read more about dingoes and children.

Do they charm you for food? Yes. This can be mistaken for affection, but if they’re doing something for food, it would be fair to say that that isn’t affection. For example, if we’re sitting down for a nice roast or barbecue, Rusty and Jalba sit or lie beside us on the floor, or slide under our arm and rest their chin on our lap. Bonus points if they look up with those gorgeous eyes. Likewise, if it’s nearly meal time or they’re waiting for a Likimat or I’m cooking, Rusty puts his paws on my feet, or they boop me, nudge me gently with their head or flick me with their ears.

Do your dingoes enjoy soft toys? Well…. Yes… but a little too much. We rarely give them soft toys. Any toy with a squeaker is a nightmare — it brings out their prey drive. Most soft toys for pets have squeakers, so if we buy one, we take out the squeaker and sew it back up. BUT there are other rescue dingoes who treat their soft toys affectionately, like Phoenix, who is simply adorable.

Should I consider adopting a dingo? If you’re after a canine companion who will give you plenty of affection, keep in mind that most dingoes are not as cuddly as dogs might be. Some dingoes are, some dingoes aren’t — they’re usually quite aloof. You can read more about adopting a dingo here.

Are dingoes affectionate?

Rescue dingoes who live in home environments are aloof and wary but can demonstrate affection towards their immediate family. Some rescue dingoes might prefer not to be touched whilst others enjoy pats and close companionship of humans they trust.

Wild dingoes avoid human interaction but demonstrate affection towards their own pack. Humans should not interact with wild dingoes — they deserve a free, wild life, and human interaction puts dingoes at risk. Never approach, feed or take a dingo from the wild. If you are concerned for the welfare of a wild dingo, please contact your local wildlife service.

Share your experience with rescue dingoes

Do you work with dingoes in Australia or have rescue dingoes in your home? Do you, or have you conducted research about dingoes? I’d love to hear from your or about your experiences — comment below or drop me a line!

Further reading:

Daly, N, 2019, ‘Domesticated animals, explained’, National Geographic, 4 July.

Dingo Advisory Council, n.d., ‘The significance of the dingo in indigenous culture’, Dingo Advisory Council

Driscoll, C, Macdonald, D, O’Brien, S, 2009, ‘From wild animals to domestic pets, an evolutionary view of domestication’, National Center for Biotechnology Information, 15 June.

Koungoulos, L, Balme, J, Ingrey, S, O’Connor, S, 2023, ‘Did Australia’s First Peoples domesticate dingoes? They certainly buried them with great care’, The Conversation, 21 October.

Purcell, B, 2010, Dingo, Australian Natural History Series, CSIRO Publishing

Ritchie, P, 2023, ‘New DNA testing shatters ‘wild dog’ myth: most dingoes are pure’, University of Sydney, 8 June.

A note on dingoes and domestic dogs

Dingoes are not domestic dogs.

The differentiation is critical, as it relates to Australia’s management of dingoes. Dingoes are formally recognised as an Australian native animal, yet are not offered the same protection as other native animals. Instead, dingoes are classified as “wild dogs”, which are actively and intentionally killed in Australia, through inhumane 1080 poisoning, trapping and shooting.

This differentiation warrants its own discussion — I’m not sure if I’ll cover this anytime soon, but if you’d like to learn more, I recommend starting with reading research by Dr Kylie Cairns.

0 Comments