Now that you’ve prowled through the archives and pored over letters, you’re as informed as you ever will be and are ready to carry out additional field research, such as interviews, observation and immersion.

Interviews as a mode of research

Warren noted that interviews in qualitative research gained traction in the 1920s and 1930s in the field of social sciences at the University of Chicago and then following this, interviews were used widely after WWII.

Hamilton stated that for a long time, interviews and oral research were considered the “least valuable” and “the most suspect” by historians. Oxford educator and writer, Professor Benjamin Jowett argued that the historians’ role was to interpret evidence, not produce it. Creating “fresh, primary archival evidence” was perceived as grunt work, something grad students would take care of, “just as barristers and courtroom lawyers got minions to look up the relevant statutes and cases”.

Its illegitimacy as a form of research is reflected in Hamilton’s experience studying history at Cambridge University in the 1960s, “none of my teachers had ever taken oral history seriously, let alone taught us how to interview”. Likewise, Carl Rollyson didn’t complete any training on how to conduct interviews, he said he had no experience interviewing prior to writing a biography “I just did it as on the job training”.

Hamilton stated that academics viewed interview evidence and oral history as “subjective, based upon fallible memory, demanding actual (heaven forbid!) personal contact between historian and source”. But this subjectivity is today seen as valuable, not just in biography but in humanities and social science too, it “is seen as rich, valuable, and illuminating”.

Nobel Laureate and oral historian Svetlana Alexievich said “I’m interested not only in the reality that surrounds us, but in the one that is within us. I’m interested not only in the event itself, but in the event of feelings. Let’s say – the soul of the event. For me feelings are reality”.

Examples of biographical interviews

Hamilton said that interviews enrich biographies; instead of creating a “monochromatic portraiture”, he is able to “use the different lenses of multiple observers to emphasise the diversity of truths about a human being”. He said that by finding and interviewing “a host of possibly competing witnesses” we can create a “multifaceted picture of the subject through diverse insights and contributions: a collage rather than a single-perspective painting”.

Caro interviewed everyone who associated with Lyndon Johnson in any way — he interviewed Johnson’s speechwriter 22 times, on the phone and through formal interviews and Johnson’s chauffeur, who spent hours alone with Johnson each day. In Santel’s interview, Caro mentioned that he asked questions to help create the scene: “What was he [Johnson] doing in the backseat? Finally, he told me that Johnson often would be talking to himself”. Caro would press further, asking what Johnson was saying, and so on. Caro drove to towns, read the local papers, visited the libraries and interviewed people who helped with campaigns.

Rollyson conducted seventy five interviews, including interviews with Lillian Hellman’s students, interviews with other faculty members and her physician.

Stacy Schiff interviewed Saint-Exupéry’s colleagues from Aéropostale, James Atlas interviewed hundreds of Saul Bellow’s contacts, Robert Caro conducted 522 interviews for The Power Broker and thousands of interviews for Lyndon Johnson’s biography.

In his research for Monty: The Battles of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, Nigel Hamilton was introduced to all of Montgomery’s family, colleagues, and subordinates. He said:

By gathering their subjective testimonies, I was determined, alongside my archival work, to achieve a fresh degree of critical perspective, veracity, and vividness in my portrait — more so, ironically, than a portrait painter, who after all, is painting in some ways in monochrome, even when he is using the entire palette of colours, for it is always via his own brush that we are seeing the subject.

Walter Isaacson carried out over 40 interviews with Steve Jobs, as well as over 100 interviews with those involved in Jobs’ life — Jobs gave Isaacson free reign to interview whoever he wished. In Josh Lowensohn’s interview, Isaacson said the interviews “almost did not feel like interviews”, with the pair engaging in conversations, such as walking in the garden.

Interviews as a gateway

A gateway to more interviews

Often, one interview can lead to another. Prior to researching Marilyn Monroe, Rollyson had worked with a director, who put him in touch with Monroe’s masseur and confidant, Ralph Roberts and also Steffi Sidney, a close contact of Monroe’s. They too then connected Rollyson with others including Rupert Allan, Marilyn’s “most important publicist”.

Hamilton had trouble gaining access to General Joseph Collins, who was an American infantry and Armored Corps commander from D-Day until the end of the war. Collins declined an interview, until “General Alfred Gruenther, Supreme Commander of NATO in the 1950s, called Collins at his Washington home and when told that General Collins was in the shower, he said “Well get him out! I’ve a young British historian here who wants to talk to him — today!”

A gateway to primary documents

Interviews are also a means of collecting primary documents. In researching Monty, Nigel Hamilton conducted over 1000 interviews and Hamilton said if the interviewee viewed him as sincere and fair, they often showed him “unpublished letters, diaries, or photographs, and often pass me on to another witness” and then that witness often brought more documents he hadn’t seen before.

Hamilton was once interviewing Montgomery’s step son, Brigadier Richard Carver, and when Hamilton asked him how his stepfather reacted to his mother’s death, Carver “brought me a folded, handwritten letter Monty had written him on the day she passed away, and which he had added to immediately after her funeral several days later. It was deeply, almost hysterically emotional, and very moving”. On another occasion, Hamilton interviewed the “son of the headmaster who had looked after Monty’s son David on school holidays during World War II” and the major said he looked in the attic and found two hundred letters from Monty to his mother.

Resistance to interviews

Not everyone is so forthcoming. When Rollyson started work on Marilyn Monroe: A Life of the Actress, he called Whitey Snyder, “Marilyn’s favourite makeup man and confidant” who treated Rollyson with “scarecely veiled hostility”. Rollyson tried to take an academic approach with Snyder, asking simple questions that wouldn’t cause offence and tried mentioning people he had already interviewed, whom Snyder respected. Rollyson said, “I tried and tried in an agonising phone call that lasted perhaps five minutes — with me doing most of the talking — and then I gave up and said goodbye”.

Rollyson said that since then, he’s always felt a reluctance when faced with making a call to interviewees; he said that Snyder had made it clear that “biographers are intruders”. Rollyson refers to interview rejections as a “troubling aspect of biography”, which is why some biographers only write about people who died a long time ago and therefore they have no one left to interview. Be prepared to be treated with “suspicion, contempt, and hostility” and potentially be threatened with lawsuits.

Nigel Hamilton sought an interview with General Matthew Ridgway, who was “the great Airborne Corps commander in World War II”, but the General declined as he had fallen out with Montgomery. Rollyson occasionally came across individuals who refused to speak because they felt they could say nothing good about Rollyson’s subjects, for example, in the case of Lillian Hellman, playwright Ruth Goetz didn’t want to be interviewed but “she could not help but whisper fiercely over the phone: ‘She was a viper!’”

Potential interviewees may face negative consequences by participating, for example, Rollyson co-wrote a biography on Susan Sontag with his wife and Rollyson said that “it was generally thought that Sontag had immense power and access to high-powered attorneys who could make life difficult for those who cooperated with us”. For example, one person had had a “terrible experience in Susan Sontag’s writing class” and when Rollyson contacted her, she wanted to remain anonymous, she said, “You see, I’m coming out with a first novel, and Susan can see to it that the book will be reviewed badly”.

Hamilton states that authorised biographers are more likely to gain access to interviewees, however not all interviewees will be fussed about whether or not the biographee has given their permission for the biography to go ahead. Rollyson flew to St Louis to interview Martha Gellhorn’s childhood friends and classmates and “only a few asked me if I had her cooperation. To them, I simply said that I hoped to get it. I did not go into any detail, and to my relief they asked no more questions”.

At times, potential interviewees may decline, but Rollyson said that such individuals sometimes changed their minds when they realised that they may be featured in a book without having had their own say.

To reduce resistance, Rollyson and his wife, Lisa Paddock, used preliminary interviews with individuals “more or less at the periphery… to build up a network of contacts” and then they sought out a publisher and interviews with more significant individuals.

Rollyson noted that Robert Caro also followed this process when writing about Lyndon Johnson, “he knew that many important figures would not speak with him if he approached them immediately, so instead he turned first to figures of lesser importance, cultivating them, and parlaying the information they gave him into interviews with major sources”.

Interviews as a means of rewriting history

As noted previously, many groups are silenced in history — their presence is nonexistent or relegated to general, sweeping statements that brush over their complexities and uniqueness — interviews, however, offer a way to compensate for the lack of secondary and primary sources.

In conducting qualitative research, Erin Jessee interviewed people in Rwanda and Bosnia-Herzegovina, and she said that by “talking with members of censored or oppressed communities in Rwanda and Bosnia, I was creating opportunities for the democratisation of history”.

Jesse said that interviews are a way of “revealing the multiple truths of people’s lived experiences and complicating the grand historical narratives that might otherwise exclude them from the historical record” — Raphael Samuel called this “history from below”.

In “Life Story Interview”, Atkinson notes that interviews can help put a spotlight on people not traditionally heard: life stories can “balance out the databases that have been relied on for so long in generational theory, researchers need to record more life stories of women and members of diverse groups… we need to hear the life stories of individuals from underrepresented groups, to help establish a balance in the literature and expand the awareness and knowledge level of us all”.

Next up: Immersion in life writing.

Image: “Marilyn Monroe with Acting Teacher Natasha Lytess” by oneredsf1. Available at Flickr under Creative Commons 2.0.

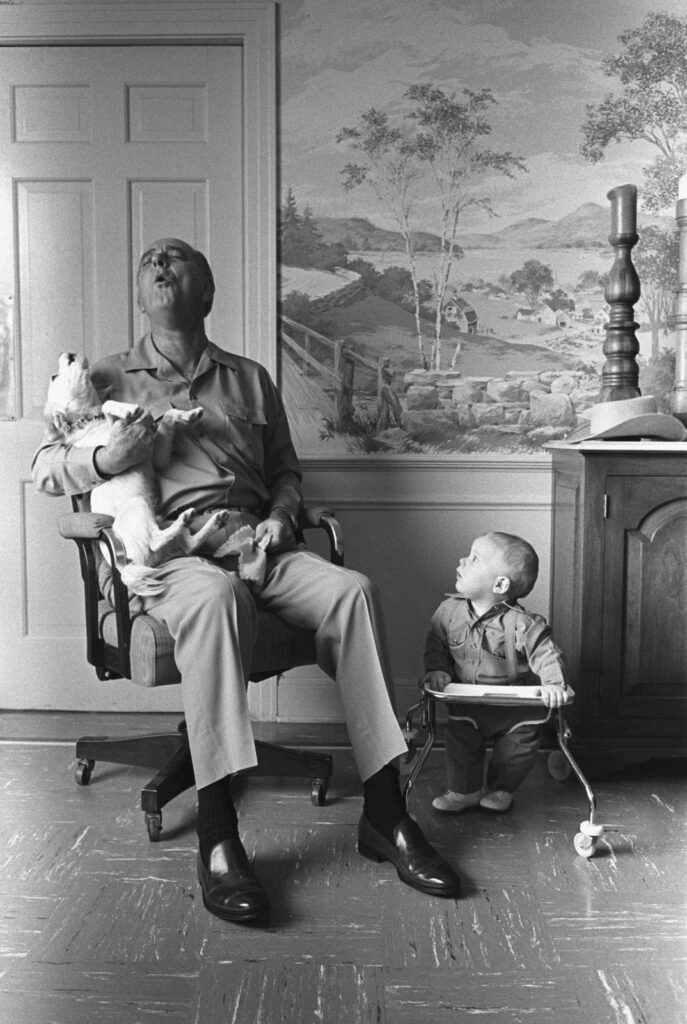

Image: “President Lyndon B. Johnson singing with Yuki”. Available at The U.S. National Archives.

0 Comments