If you’re reading this article, it’s likely because you’re flirting with the idea of writing a biography, but aren’t sure where to start. Your apprehension is well founded, given it can take several years to research a biography.

Biography is a crazy courageous endeavour, both for the biographer and the subject. Biographer Paula Backscheider estimates that a well-researched biography takes five to fifteen years of research and writing. Biographers have been known to spend two years researching, others five, and others, even more: James Boswell studied Samuel Johnson for well over twenty years. Twenty years. Two decades. That’s a mighty long time.

To immerse oneself, studying one person for this length of time would border on obsession. Backscheider describes the biographer as needing to “live with their subjects as parasites and barnacles, attempt to follow them day by day, study their relationships with everyone, pore over their letters and diaries, pounce upon all descriptions of them, if possible sit in their chairs and handle their crockery.”

Janet Malcolm’s description of a biographer is noteworthy: a biographer is like “a professional burglar, breaking into a house, rifling through certain drawers… and triumphantly bearing his loot away.”

Whether you spend five years or twenty, to spend so much of one’s life studying one human being demands a level of obsession, dedication and intimacy – and a biographer must have a very well justified reason for embarking on such a quest. Your initial research using secondary research will help you find that reason — I’ll cover this below. In later articles, I’ll discuss how biographers have found primary evidence and. I’ll also discuss how to create new evidence, which isn’t as shifty as it sounds!

Before you commit to writing a biography

Researching and writing a biography is a deep, intense undertaking, most definitely not a commitment that one should jump into without knowing the complexities of their new bedfellow (Hamilton 2008). Nigel Hamilton, biographer of Bill Clinton, John F. Kennedy, Thomas Mann and more, said that when writing a biography, we live in cohabitation and this “requires you to have some prior conviction as to why you think this is the right person for you to spend years of your life with”.

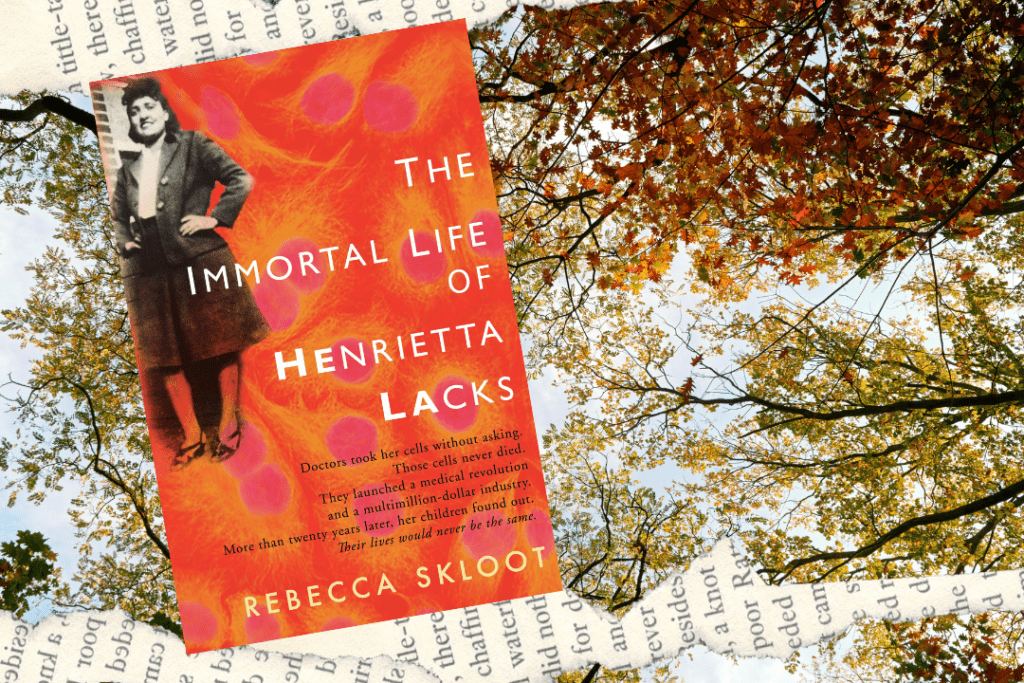

Hamilton spent over ten years researching and writing Monty: The Battles of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery; Lee Gutkind stated that Rebecca Skloot researched and wrote The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks over thirteen years. Damian Garde states that famed biographer Walter Isaacson is said to spend two years researching and two years writing, which isn’t nearly as terrifying as James Boswell’s twenty years.

Before you fully commit, get to know your new companion by carrying out preliminary research: read what work is already out there; draw up a list of positives and negatives of the person and consider if you’ll be able to find enough information to write a biography — for example, is there a plethora of published and unpublished documents that you can access, people you can interview? Start defining how your biography will differ from any that already exist, and who your audience will be.

Preliminary research

Now this is where you start to delve into who this person really is, without having to commit too much. The amount and type of research undertaken will always depend on a number of factors, such as cost, time, priority, access and motivation.

Research for biography mirrors research for history in the sense that biographers search libraries and archives for information that can be verified, however a key difference in researching biography is that the individual is front and centre, and the context of their life, such as the social, political and environmental times in which they lived, is secondary.

In researching biography, Nigel Hamilton recommends starting with secondary sources: that is, information which is already published, followed by primary documents such as unpublished manuscripts and letters, followed by interviews, which is, in effect, creating primary evidence. Additional methods of research include observation and immersion, which will also be discussed in this series of articles.

Secondary evidence

Secondary evidence includes sources which were produced to analyse primary sources and are generally easy to access. Examples of secondary evidence include books, newspapers, journal articles, dictionaries and magazines.

Hamilton suggests reviewing published biographies about your biographee, as well as the bibliographies, footnotes and endnotes of these biographies. Consider also checking the author’s foreword and acknowledgements. Search libraries, archival reference books, analyse published photos, videos, news clippings, museums and biographical dictionaries such as the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, American National Biography or the Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani.

In an interview with James Santel, Pulitzer Prize winning biographer, Robert Caro said “First you read the books on the subject, then you go to the big newspapers and all the magazines—Newsweek, Life, Time, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Washington Star, then you go to the newspapers from the little towns. If something appeared there, you want to see how it’s covered in the weekly newspaper”.

As you conduct your research, keep a research log and as Hamilton said, remember that there is not “ever a single (let alone simple) truth”. Have humility and be honest – you may discover that the person is not who you thought they were. In the book Understanding Biographies, Birgitte Possing described how Virgina Woolf stressed that biographies should be tied to sources and fact, even if the facts contradict our ideas of our biographee’s life.

If you decide at this point, that this relationship should end, so be it. Two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, David McCullough ploughed into researching and writing a biography of artist Pablo Picasso, but ceased because “I found I disliked him so. He was, to me, a repellant human being, and he didn’t really have the story of the kind that interested me… I found he wasn’t somebody I wanted to spend five years with as a roommate, so to speak”.

The never-ending story

At the other end of the spectrum, once you’ve started down that rabbit hole of research, it’s important to know when to stop. In an interview with The Paris Review, Stacy Schiff said:

The years in the archives can feel endless, as if you’re on an eternal grocery-shopping expedition and will never actually cook anything. If ever you were actually a writer, you are no more. You’re more like a sponge, with all the personality of one. Finally one day you wake to discover sentences forming in your head, the signal that it’s safe to leave the archive.

In searching the LBJ Presidential Library, Robert Caro said, “there’s no hope of reading it all. You’d need several lifetimes” — you need to know when to stop researching. In “The New Statesman”, Hermoine Lee said “you can only access them in as far as you have materials and witnesses to allow you to access them. You are at the mercy of what you can find and read and hear and see. You become as intimate as you can with the life and work of this person… But there is always going to be a gap”.

There can never be a complete biography, even more so when your subject is still alive when you are writing. As Hermoine Lee said about her biography of Tom Stoppard: biography is open-ended, “in 50 years’ time, someone may write a completely different book about him”.

To learn more about researching biography, consider Hermoine Lee’s Biography: A Very Short Introduction, Nigel Hamilton’s How To Do Biography and as well as Cline and Angier’s The Arvon Book of Life Writing.

Next: Primary evidence: prowler in the archives.

Image: “Three Musicians” by Ralph Daily. Available at Flickr under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0. Full terms at Creative Commons 2.0.

0 Comments