Just how truthful is biography? And what about authorised biographies — are they really more accurate? Time to look at burglars and warts — all the good stuff!

When we see the term biography, we can assume that the work is factual, but

keep in mind

that facts are facts and

not everything in a biography

is fact.

Biographies are rarely complete works of nonfiction, in fact, you’d probably lose interest in a factual biography faster than I can say “out like a light.” Biographies which only include facts are a valuable source of information, but in terms of readability, they’re pretty dry.

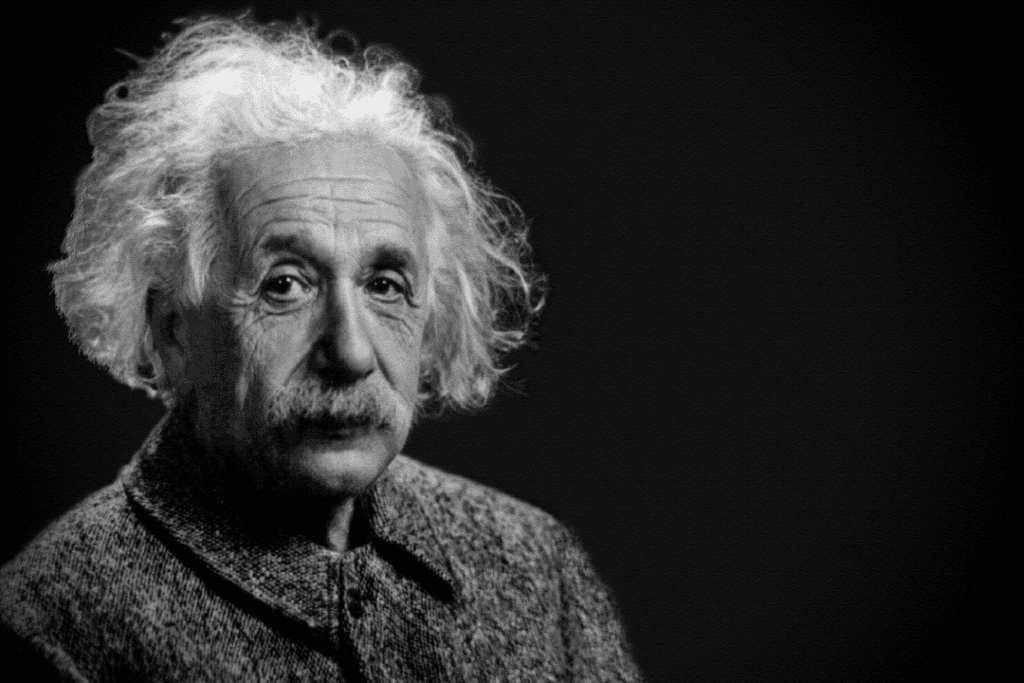

Biographers Renders, de Hanne and Harsma said that biography is not simply the “reconstruction and retrieval of facts – why would you do so with the internet at hand?” Google, Siri or Cortana can help you find out which year Einstein was born or how many Super Bowls Tom Brady has won.

So if biography isn’t pure nonfiction, what is it? Fiction? Academics haven’t always agreed, but it would be reasonable for us to say that because biographies are about events that have already taken place, biography is closely related to history and in addition, often biography is categorised under Life Writing, anthropology, social studies, literary studies, journalism and creative nonfiction.

The truth and nothing but the truth?

The credibility of biography relies on thorough, journalistic research and objectivity. Biographers take an academic or journalistic approach to their research, with high standards, including the ability to critique their sources and material.

They consider if their sources are reliable, such as by considering the source’s motivations and their relationship to the subject. Biographers verify facts, such as confirming if a ship arrived at port on the same day as told by the source. They consider documents and letters, who produced them, why they were able to access them and which ones might be forged or missing.

We must remember that information can never be taken at face value; Cline and Angier stress that records can be wrong, that people lie to census takers and that letters and diaries are kept for all sorts of reasons, and Renders reminds us that even documents and events “come to us in an institutionalised manner and through institutions in which people are not equally represented”. Consider the atrocities that governments and organisations may try to hide, by destroying documents, or only allowing access to the less incriminating ones?

Consider social media: users curate their profile, choosing what image to project – likewise, history can be influenced by the image people or groups want to be remembered by.

Biographers draw upon a wide range of research and evidence, such as official documents (birth, marriage, death certificates), letters, emails, photos, court records and interviews. Interviews are a valuable source of information, but even then, memory isn’t perfect – Angier said that “memory is unreliable… [memories] decay, are repressed and forgotten. They are replaced by the stories we hear and tell, and the photographs we see.”

This reliance on qualitative research and the involvement of the biographer as a selector and interpreter gives rise to the concern that biographies are not objective. De Haan states that in the 1930s, historians referred to biographies as novelistic and labelled biographies as biofiction, they claimed that writers were not objective and that their feelings, ideas, intellectual and moral prejudices were being projected in their work.

While today’s biographies have greater credibility than in the 1930s, it’s hard to imagine any biography as being truly objective: biographers choose where to search for information, what to include and exclude, as well as how to present that information.

Warts and all

Part of the beauty of a biography is being able to show the person as a whole, including the parts that they may not want the world to know, their weaknesses, mistakes, regrets and controversies. Failure to include the negatives is something Cline and Angier referred to as airbrushing, or making polite conversation, which doesn’t do justice to the person, given that often our weaknesses and mistakes are what cultivate our character.

Back in 1891, James Boswell published a biography of his mentor, Samuel Johnson. A writer and critic, Johnson gave Boswell permission to research and write as he wished – there were zero restrictions, because Johnson believed that there was much that people could learn from a person’s mistakes, not just their success. Boswell’s biography became known as an outstanding piece of work.

Likewise, Steve Jobs commissioned an authorised biography by Walter Isaacson, who also wrote biographies about Einstein and Benjamin Franklin. Jobs gave his biographer full reign to research and write at his discretion. Jobs enforced no limits on Isaacson, going as far as to actively encourage his friends, family and colleagues to speak openly. He didn’t control the content of the biography and didn’t even review the manuscript before it was published. The result was raw – truthful, a result of both Johnson and Jobs being content to have a “burglar in the house”, a term coined by Janet Malcolm.

At first, it’s easy to assume that authorised biographies are more accurate, that they contain more in-depth information than an unauthorised biography. On the one hand, biographers who write with the permission of their subject, should, in theory, have better access to the person, enabling the biographer to capture details that other biographers could not. In the cases of Johnson and Jobs, this might be the case, but in many cases, “authorised” indicates the subject has influenced the book, potentially censoring or skewing the angle of the manuscript.

In granting an authorised biography, the subject might assume that they can have full control over the biography, when in reality, they only have control over facts and their own accounts included in the book. The subject has no right to influence what others have said, or dictate what the writer will or will not include, such as content that may reflect poorly on the subject. The issue with this is that excluding the negatives creates an incomplete picture – weaknesses are a pivotal part of who we are: if we are perceived as successful, to deny others a full picture of what led to that success is a disservice. Renders suggests that the best time to write a person’s biography is ten years after they have died, because the subject’s peers are still alive and have been able to temper their thoughts objectively through time and the subject is no longer able to influence the content.

Renders reminds us that a biography is not a selfie: if the subject seeks to have complete control over the content in their biography, they should write an autobiography; Renders said, “a good biography is not a book of praise”. Similarly, Nicholas Murray, in Cline and Angier, said that readers should be wary of “authorised” biographies – and that biographers “should be free to write independently with no constraints and no fear of upsetting anyone.”

In reality, this won’t always be possible: biographers won’t always want to rock the boat, they may be seeking to honour a subject or show respect for living friends and family. Biographers write with the knowledge that their work won’t always be received well, for example, Andrew Morton wrote biographies about Tom Cruise and Angelina Jolie and was faced with reluctant publishers who feared legal action from the subjects. Similarly, Nigel Hamilton completed a biography of Franklin D Roosevelt in which Winston Churchill was portrayed controversially, resulting in publishers in the UK refusing to publish the manuscript.

Next up: Biographies: only about famous people?

0 Comments