Microhistory may not be a term you’ve ever heard of, but no doubt you’ve read or watched stories which were inspired by or could be defined as microhistory. Stories centred on microhistory are sprinkled throughout literature and pop culture, such as the feature film Hacksaw Ridge — but we’ll come to that later.

What is microhistory?

Microhistory takes an in-depth look at a specific person, event, moment, community, or object. I find that the simplest way to think of it, is like looking through a microscope. While history in general looks at historical events on a broad, more general scale, microhistory focuses on one key element, in great detail.

Richard D Brown defines it well, by telling us that history, at a broad, macro-level, it is as if biologists are judging “the cleanliness of a lake by looking over the side of the boat” whereas microhistorians look more closely, by taking “an ounce of the water for microscopic and chemical analysis”.

What’s so special about microhistory?

I know, it sounds a little nerdy – but consider for a moment – what if, in one or two hundred years, your story no longer exists? Imagine if, instead, your generation is defined in history books with a broad, catch-all definition, a definition that may capture your essence… or maybe not: “Australian, middle-aged men in the decade leading up to 2020 typically wore board shorts, singlets, an iconic pair of flip flops and the obligatory beard. Their main past times included late nights at the pub, Sunday afternoons with a beer and a barbie and shouting profanities at Sunday drivers. Known for their complete disregard for beard hygiene, it’s no wonder that the birth rate declined in this decade.”

Granted, today, we have many ways of keeping records, whether it be a blog, website, social media, online or print magazine, or even a handwritten journal – so it’s unlikely your generation will be defined so narrowly – but if you think about what we know about ancient Egypt, you’ll start to understand why microhistory matters.

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, chief editor of The Journal of Egyptian History, highlighted that what we know about ancient Egypt is largely based on official, recorded histories. The problem with this, is that there’s no way to know how censored or strategically planned these documents are: do they really provide an accurate insight into ancient Egyptian lives or were they influenced by politics or popular opinion? Moreno Garcia suggests we look at gender: take women, for example – there are quite a few records about elite women in ancient Egypt, but it would be presumptuous for us to assume that the experience of elite women in ancient Egypt reflects the lives of all ancient Egyptian women, just like most women in Australia don’t live like Rebecca Judd or the Real Housewives of Melbourne.

Microhistory helps us balance the dominant narrative and provide additional insights which may paint a more accurate historical picture, or at the very least, allow us to question and build upon what we already know in history.

We are one, but we are many

So now, you’re probably thinking that both types of history have the same problem: one individual can’t reflect the lives of many.

What’s interesting, is that prior to the existence of microhistory, it was thought that the experiences of the masses, a representative sample, was more important than the experiences of individuals. Some historians argue that it’s important to link microhistory to macrohistory, to justify its relevance – but in doing so, they imply that individual histories don’t matter, that is, that your history doesn’t matter. How does that make you feel?

Thankfully, a global field of researchers say that we matter.

Historians, Magnússon and Szijártó, put it well, “microhistorians don’t care about how the general population lived their life, only how their subject lived”.

Microhistory is not about creating a unified, collective past. Historian Sabina Loriga said microhistory is about enriching history with the “orchestral score” of multiple voices. She said:

…it is not necessary that the individual is seen as representative or typical for something wider. On the contrary, lives which deviate from average seem to offer a better way of thinking about the balance between specificity of personal destiny and society as a whole. Variety is more important than typicality.

By taking a micro perspective of history, such as studying one individual, we can gain deeper, more complex insights into everyday life and the prevailing customs and values, at a grassroots level.

Only famous people matter

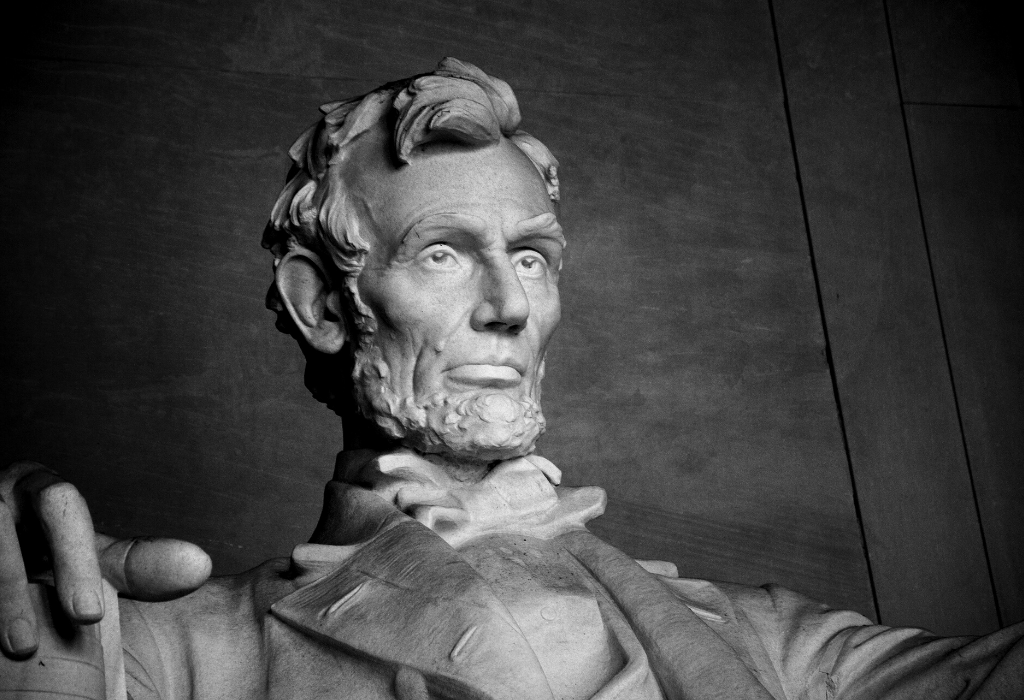

You and I both know that not only famous people matter, but our bookshelves and media libraries tell another story. Did you know that there are over 10,000 biographies documenting the life of Abraham Lincoln? Suffice to say, Abraham Lincoln was a profoundly influential leader who made a significant impact during his lifetime, so it’s expected that people are curious about all aspects of his life – but what about the lives of others?

Biographers Sally Cline and Carol Angier state that “fiction can be about ordinary people, but life writing is about extraordinary individuals (or ordinary individuals in a special time or place.)” They say that “writing autobiography, biography and memoir is by definition dramatic and special because: in biography, it is easier to write about special people or those to whom something interesting happened to them than it is to write about people who lead ordinary mundane lives”.

But isn’t there magic in “ordinary, mundane lives”? Moments that take our breath away, imprinted in our minds forever or change the course of our lives?

Some historians, such as Moreno Garcia, say that microhistory is about giving a voice to the voiceless: an opportunity to research and write about people who are not, by history’s standards, significant or visible, such as farmers, herders, minorities, low skilled workers and the impoverished. Richard D Brown cites examples of this, including the work of early Italian and French microhistorians, who studied “deviants and peasants, giving a voice to people who had hitherto been silent”.

One of the first microhistorians was Carlo Ginzburg, who, in 1976, published a study of a sixteenth-century miller, known as Menocchio. Menocchio was considered a member of the peasant class; he was not normally someone who would be visible in the history books – but Ginzburg used documents from Menocchio’s trial to create his publication, The Cheese and the Worms.

The book covers the investigation of Menocchio during the Roman Inquisition, during which Menocchio was labelled a heretic and burned at the stake. Ginzburg recognised Menocchio as representative of the times, that is, that his experience was common; while other microhistorians argue the opposite – that Menocchio and his experience are an *exception”. Exception or not – Menocchio’s experiences and Ginzburg’s study enrich our understanding of Italian history.

I think it’s safe to say that Menocchio’s was not an “ordinary, mundane” life, but that he was someone who was somewhat voiceless. I agree that failure to include the voiceless in our history is a considerable omission from our history archives, which is one reason why I’m drawn to microhistory.

So the question was, what is microhistory? Think of a microscope: it doesn’t matter what you’re studying, the key factor is that the historian is looking at a specific subject with great detail. Brown, Magnússon and Szijártó all make it clear that microhistory is more about taking a microscope to specific people (events etc.), regardless of who they are and how important they are deemed to be by society. So it’s not just about giving a voice to the voiceless, or writing about everyday people, but these stories do shape our understanding of history.

Microhistory in modern culture

Microhistory can overlap with other forms of writing, such as biography, memoir, life writing and historical fiction. Magnússon and Szijártó mention some on-point works of microhistory, such as Robin Hood, by Sir James Holt; James Shapiro’s 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare and George R Stewart’s Pickett’s Charge: A Microhistory of the Final Attack at Gettysburg, July 3 1863.

Shapiro’s work may be particularly interesting for literary buffs, as the book examines the year that the Globe opened and when Shakespeare began writing Hamlet. Stewart’s Pickett’s Charge looks only at the fifteen hours leading up to the failed attack at Gettysburg. In each case, the author has taken the microscope to a specific topic and in Stewart’s case, significantly limited the scope of the work to just those key fifteen hours.

Well-known memoirs such as Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl, Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning and Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave may be considered as microhistory – but would it then be fair to say that all biographies are microhistory? I guess that would depend on your definition of microhistory, which historians never seem to be able to agree on.

Although many historical films are works of fiction, some can be identified as being related to microhistory. The feature film, Hacksaw Ridge, is a work of creative nonfiction (a fictional story based on true events) which centres on one individual and events that take place over a short period of time.

Where to from here?

A hundred years from now, a thousand years from now: it would be regrettable if future generations were to see us only through generalised descriptions of the whole, our faces and stories blurred behind the lines on the page, our challenges and triumphs buried without meaning.

Richard D Brown said that “microhistorians recognise that every event embodies a kind of existential moment in which the course of history intersects with individual action”. Inspired by microhistory, I recognise that every person has these moments, and regardless of how prominent society judges them to be, these stories deserve to be told.

Cline and Angier said that “everybody has a story. And if a writer tells that story well, it is as fascinating as good fiction – or even more.”

*The debate about microhistory and the importance, or not, of being an exception is one for another day.

Further reading:

Brown, RD 2003, ‘Microhistory and the post-modern challenge’, Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 23, no. 1, pp.1-20.

Curthoys, A & McGrath, A 2009, How to write a history that people want to read, UNSW Press, Sydney.

Gamsa, M 2017, ‘Biography and (Global) Microhistory’, New Global Studies, Vol. 11, Iss. 3., pp. 231-241.

Loriga, S 2017, ‘The Plurality of the Past: Historical Time and Rediscovery of Biography’ in H Renders, B de Haan & J Harmsma (eds.), The Biographical Turn: Lives in History, Routledge, London.

Moreno Garcia, JC 2018, ‘Microhistory’, in W Grajetzki & W Wendrich, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.

Magnússon, SG & Szijártó, IM 2013, What Is Microhistory? Theory and Practice, Routledge, London.

Peabody, S 2013, ‘Microhistory, biography, fiction’, Transatlantica, vol 2., 2012.

Peltonen, M 2014, ‘What is Micro in Microhistory’, in H Renders & B de Haan (eds), Theoretical Discussions of Biography: Approaches from history, microhistory and life writing, Pictoright, Amsterdam.

Magnusson, SG 2017, Do you know what microhistory is all about?

Stearns, P 2017, ‘Social History’, Oxford Bibliographies.

Image: “Carlo Ginzburg” by Claude TRUONG-NGOC available at Citazoni e frasi celerbi under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0.

0 Comments