From burning letters to sealed trunks and rescuing papers from the Thames, tracking down primary evidence isn’t for the weak. Let’s look at the challenges of using primary evidence, from finding it to gaining consent, as well as the successes a few biographers have had, including Walter Isaacson, Hermoine Lee, Robert Caro and Stacy Schiff.

Once you’ve delved into secondary evidence, and you know you’re ready for the commitment, consider searching for primary evidence.

But a quick side note: these articles are not a chronological process for researching biography. There are other essential steps to take before delving into deep research, such as obtaining consent to write the biography. It’s not something I’ve researched much, as yet, so I won’t cover this in this article — but remember to consider if you need to gain consent from your biographee or that of their family or friends.

Your research using secondary evidence would have been a rich starting point in your research. Now it’s time to invest more time and resources into really knowing your biographee. It’s time to dig deeper, searching for and examining primary evidence, before embarking on the creation of new, primary evidence. In Santel’s interview, Robert Caro said these are the first steps, “the books, the newspapers and magazines, the documents. Then come the interviews”.

Primary evidence: unpublished documents

Primary evidence includes sources which are first-hand accounts, these include unpublished documents such as letters, notebooks, films, photos, oral history, unpublished manuscripts and articles, essays, diaries, medical records and more.

In an interview with Lisa Cohen, biographer Michael Holroyd said that he believes in “the magical as well as the meaningful – in seeing the actual documents, in one’s hand, actually touching the paper”.

Likewise, Hermoine Lee was one of the first to see personal documents belonging to Penelope Fitzgerald, some of which had been “rescued from the river when the barge that she lived on sank in the Thames. It’s moving to hold these crinkled copies with her writing on them”.

Primary evidence can be a valuable source of information when researching groups which are largely unpublished, for example, when researching women from the 17th and 18th centuries. Biographer Hermoine Lee stated that during these times, many women wrote “poems, plays, novels, diaries, letters, travel writings, essays, and hymns” but memoirs of these women are hard to come by.

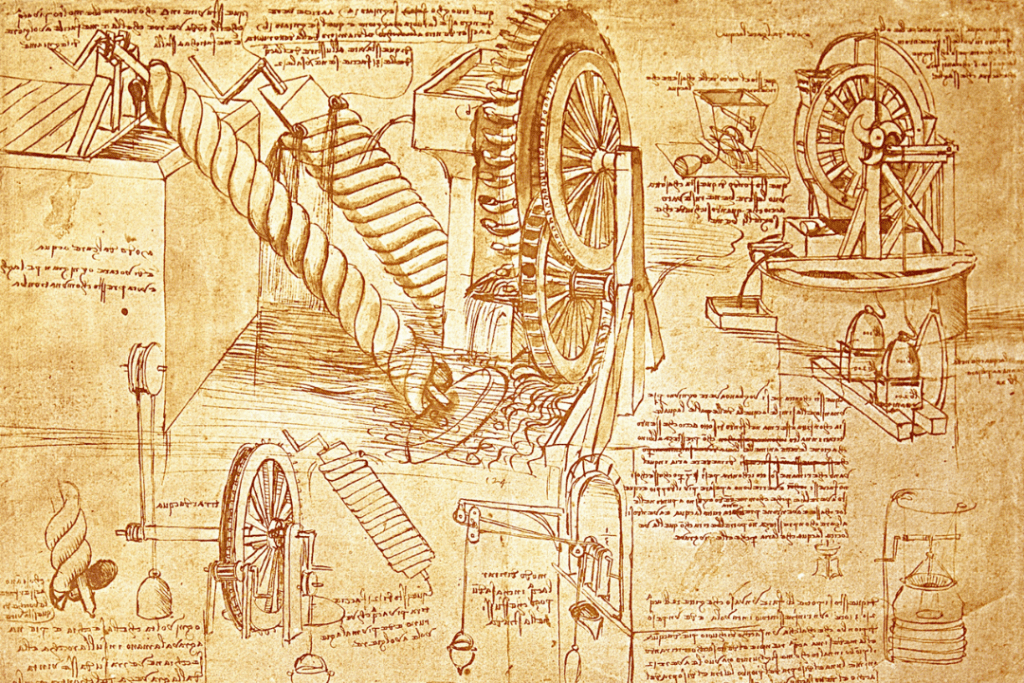

Imagine leafing through treasures such as Leonardo Da Vinci’s notebooks, Ernest Hemingway’s letters, George Orwell’s papers or HG Wells’ unpublished autobiography… There are immense treasures to be discovered — the challenge is to find them, access them and obtain permission to actually use these sources — but first, let’s look at those who have found success in archives.

Success in the archives

Given the need to travel, official archives may be difficult to access, however over time, more records are becoming digitised, enabling access regardless of where you are. There’s an endless number of official archives located worldwide.

Myrna Oliver wrote that J.D. Salinger’s letters are archived at American universities including Princeton, Harvard and the University of Texas, as well as with Salinger’s former publisher. Oliver noted that biographer Ian Hamilton was able to read and analyse these letters but unfortunately due to Salinger’s opposition and subsequent legal action, Hamilton was not able to quote from the letters.

Walter Isaacson accessed Leonardo Da Vinci’s notebooks, “more than 7,000 pages still, miraculously, survive… Leonardo crammed every page with drawings and looking-glass notes… math calculations, sketches…” Isaacson said “I love his to-do lists, which have entries like “describe the tongue of the woodpecker”.

In researching iconic poet and novelist Sylvia Plath, Carl Rollyson accessed Plath’s archive at the Mortimer Rare Book Room at Smith College in Massachusetts, including Plath’s mother’s letters and Plath’s original writing, “as she first set them down on the page”.

In his interview with Santel, Robert Caro discussed his four volume biography about US President Lyndon B. Johnson. Caro said he was able to access vast archives, with an entire library dedicated to the late president. The LBJ Presidential Library in Austin, Texas, houses papers by Lyndon B. Johnson and those he associated with, such as Roosevelt, Truman and Eisenhower. Caro said that the library houses “forty-four million pieces of paper. These shelves go back, like a hundred feet. And there are four floors of these red buckram boxes. His congressional papers run 144 linear feet. Which is 349 boxes. A box can hold eight hundred pages. I was able to go through all of those, though it took a long, long time”.

Caro spent three years searching those archives and Carl Rollyson dedicated four years to searching Amy Lowell’s archive at Harvard University’s Houghton Library.

In an interview with Ruth Franklin, Pulitzer Prize winner Stacy Schiff discussed her biography of writer and aviator, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Although there wasn’t an official archive of Saint-Exupéry’s documents, the national library of France, Bibliothèque nationale de France, held some of Saint-Exupery’s manuscripts and Saint-Exupéry’s friends and family also had documents. Schiff said “his letters were delicious, as was every scribbled note and inscription”.

Anna Leszkievicz described how Hermoine Lee examined Virgina Woolf’s letters that hadn’t been viewed by anyone else before, “simply by asking the right person”. David McCullough also referred to letters, and famed biographer James Boswell included Samuel Johnson’s letters in his biography of Johnson.

Nigel Hamilton, the official biographer of Field Marshal Montgomery, had “unique access to his private as well as official papers, including diaries, memoirs, telegrams, letters, manuscripts”.

Rollyson found useful information about writer Martha Gellhorn in H.G. Wells’ unpublished autobiography and eventually “material came flooding my way without my really trying to find it” including letters and photographs of Gellhorn. Mary McVicker found very little published information about artist Adela Breton, but was able to use letters that Breton had written and received. McVicker visited museums which housed Breton’s letters and each museum was able to refer her to other institutions which held more letters.

Challenges: prowler in the archives

The inability to access primary evidence may cause publishers to be reluctant about signing onto a biography — Hamilton stated that it’s imperative that biographers can demonstrate how they will be able to access primary evidence and gain permission to use it.

When Ian Hamilton sought to write J.D. Salinger’s biography, “not only did Salinger refuse to cooperate or give copyright permission for his writings to be quoted; he made it legally impossible for any of his relatives, friends, or colleagues to be interviewed”. Hamilton’s biography of J.D. Salinger was blocked by the U.S. Supreme Court, and Hamilton subsequently wrote and published In Search of J.D. Salinger, which is not Salinger’s biography, but Hamilton’s account of his quest to learn more about Salinger.

Rollyson also wrote a biography on Lillian Hellman, a distinguished American playwright, screenwriter and author. In attempting to access her archive in Texas, Rollyson discovered that Hellman had restricted her archive to only her authorised biographer. Fortunately Rollyson was able to find other primary documents which were not located in the archive, including hundreds of letters, a screenplay and her husband’s diary.

Rollyson stated that novelist Henry James “burnt his letters to foil future biographers”. American writer, Willa Cather, wrote in her will that her letters never be quoted, resulting in Hermoine Lee paraphrasing Cather’s letters, which would have been more effective had they been quoted.

In some instances, archives exist but are not yet available to the public. When researching novelist and journalist Martha Gellhorn, the John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library released letters that her husband, Ernest Hemingway had written to Gellhourn and her mother.

In viewing these letters, Rollyson realised that he had to alter his work — he had to “provide a more subtle, more nuanced view of the marriage. If Hemmingway was a beast, he was also an ageing, vulnerable beauty”. Rollyson noted that Gellhorn also placed a caveat on her letters housed in the special collections department of the Mugar Memorial Library at Boston University, preventing anyone from accessing her papers until 25 years after her death.

Ruth Franklin wrote about Stacy Schiff’s success in finding archival information about Saint-Exupéry but noted that when Schiff sought to get hold of papers from Saint-Exupéry’s mistress, rather than provide access, she sealed her papers at the Bibliotheque nationale de France and “with great glee she informed me that they would remain unavailable until after I was dead”. On a similar note, Rollyson stated that Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath’s husband, sent “a trunk to Emory University that is sealed until 2023. Who knows what is in it?”

Even if you can access these coveted archives, there’s also the question of consent — gaining permission to publish or quote from papers and documents. Nigel Hamilton described how Bernard Crick wrote George Orwell: A Life and was able to secure consent from Orwell’s widow, Sonia. Crick had access to Orwell’s documents and permission to quote as he pleased, however, upon completion of the manuscript, Sonia didn’t approve of the manuscript and unsuccessfully sought to remove the permission previously given.

Robert Newman wrote Cold War Romance: John Melby and Lillian Hellman. Rollyson noted that Newman worked closely with Melby on the book — Melby had the late Hellman’s letters and Newman thought that because Melby had them, that he could quote from them, however Rollyson reminded Newman that he actually needed permission from Hellman’s estate, which he eventually got, with “severe restrictions on the amount of material he could quote”.

There’s a certain intimacy about exploring archives and leafing through original letters – something which may become less frequent for future biographers. With the change of technology, letters are a rarity, with communication fleeting, easily deleted and widely spread through a plethora of apps.

The late biographer, James Atlas, stated that research would be different in the future, with many archives accessible at our fingertips, emails “will yield both more and less than a single letter” and with self-censorship there will be “less evidence of the emotional perturbations”. Manuscripts, drafts, works in progress will be “in the cloud”… but we will be missing the “joy of tactile discovery – the very thing that keeps us going”. Considering all my drafts are “in the cloud”, I think he might be right.

Up next: Using interviews in biographical research.

Image: Leonardo Da Vinci’s sketch of his intricate design for water wheels and screws to be used in an irrigation system. Available at Wikimedia Commons and is in the public domain.

Image: “Salle Ovale (Oval Room) of the National French library, Richelieu building” by Poulpy. Available at Wikimedia Commons under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0.

0 Comments